2 D-WBL approach

As has been explained before, the development of this guideline is based on Gathering good practices, stakeholders experiences and literature insights a VET Practice Evaluation. All this knowledge goes hand in hand with the answer given to four key questions: What do we mean by digital WBL? What is “good” digital WBL good practice? What (good) practices are there of digital WBL? and What are digital WBL scenarios?

We can find below a brief answer to these questions, that are present throughout the guidelines.

2.1 – What do we mean by digital WBL?

Digital support, provision and/or enhancement of practical experiences in a vocational context for knowledge and skills development as well as integration of theory and practice.

Based on this definition, we can say that digital WBL includes various learning situations in which two specific elements can be distinguished:

– the use of a learning approach based on practical experience (including laboratory activities, work-based learning, experiential learning, etc.)

– the use of digital solutions to support the implementation of hands-on learning. The presence of digital can thus be of different types and intensity: from the communication platform, to computerized systems and tools to support the implementation of practical work, to virtual environments where experiential learning takes place through the use of simulators.2.1

2.2 – What is a “good” digital WBL good practice?

There is no simple single answer to such a complex question. It depends on several context factors, and each one (or better, each team) must find their particular useful and well-based answer.

This guideline can help to narrow answers and to improve D-WBL practice experience.

Section 3 gives a panorama of the principal good practice characteristics, emerging from literature and stakeholders contributions. This section allows interested people to go in depth into all the relevant topics for digital VET, such as what are stakeholders and conditions for successful WBL implementation or who and what do we need to take into account.

Section 3 prepares the field to Section 4, where the VET practice evaluation tool (VPET) is presented.

The VPET wants to be a useful tool to realize how a digital VET practice is designed and implemented, highlighting those aspects that could be improved. Section 5 provides some examples of application of VPET to real practices, chosen as good practices by international stakeholders, allowing this guide to answer the following question as well:

2.3 – What (good) practices are there of digital WBL?

Section 5 presents some good practices, gathered from different European countries, with a brief description of them and some criteria used to consider each one as a good practice.

It is precisely the variety of contributions and experiences that feed this work that leads to the argument mentioned above: a good practice depends on several context factors.

But the principal aim of the D-WBL project and of this guide is to boost VET practice experiences. So, we have defined three scenarios, and we would like to invite all the readers of this guide to go a step further through them to improve their experience in D-WBL:

2.4 – What are digital WBL scenarios?

The acceleration given by the pandemic situation to the digitisation of learning systems has opened up new development scenarios, to the point where it is difficult to imagine a downgrading of the developments achieved so far.

In the vocational and adult education system, new challenges and complexities are rapidly emerging with respect to the way digital learning is designed, delivered, managed and certified.

The area of experience-based learning (into which the work-based learning methodology is included) has been one of the areas most affected by the challenges and, at the same time, most urged to experiment with new technological solutions to virtually re-create the work environment.

Virtual reconstruction must be careful to configure both the hard component of the work environment (i.e. the tools, the industrial machinery, hence the object of the work), and the more socially dynamic components (the work environment as a learning environment through observation of the behavior of more experienced colleagues, exchange of solutions among peers on possible problems to be solved, corporate knowledge management, etc.).

While on the one hand there are solutions to virtually recreate and make accessible any working environment from ‘remote’ (there are technologies such as augmented reality, virtual reality, metaverse to reconstruct such environments) and innovative pedagogies can support the teacher to use such environments in learning processes, on the other hand, in the practice of distance learning, the solutions do not seem to be within everyone’s reach.

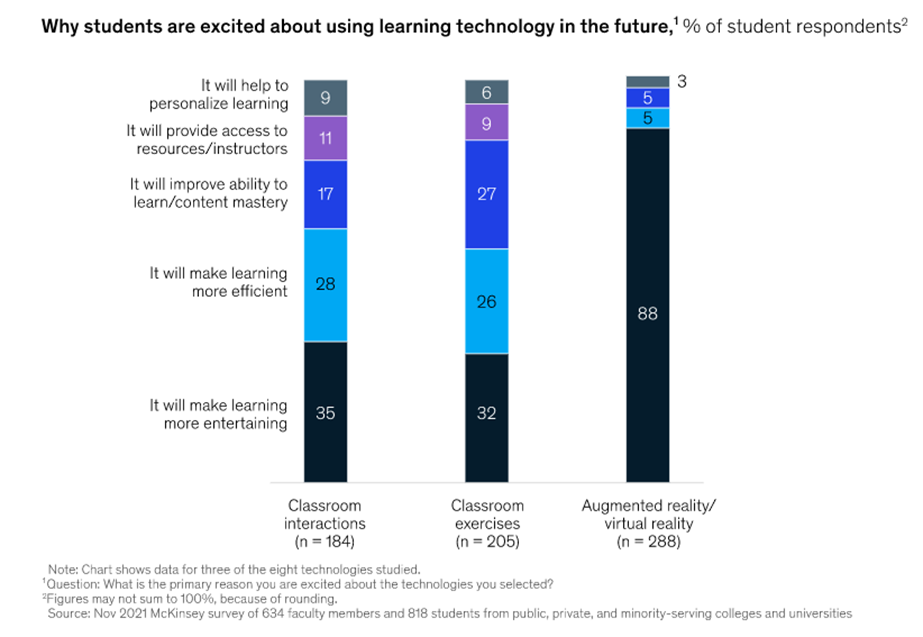

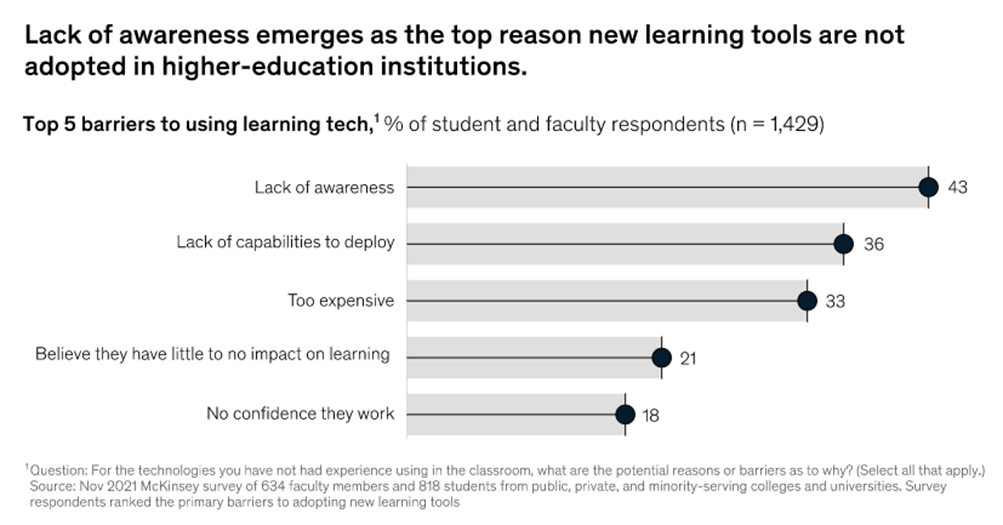

Recently, the survey conducted by McKinsey (2022) on “How technology is shaping learning in higher education” highlights some of the reasons why students may prefer educational offerings using advanced technological solutions in the future, and why these are not widespread.

Source: Mc Kinsey & Company “How technology is shaping learning in higher education”[1]

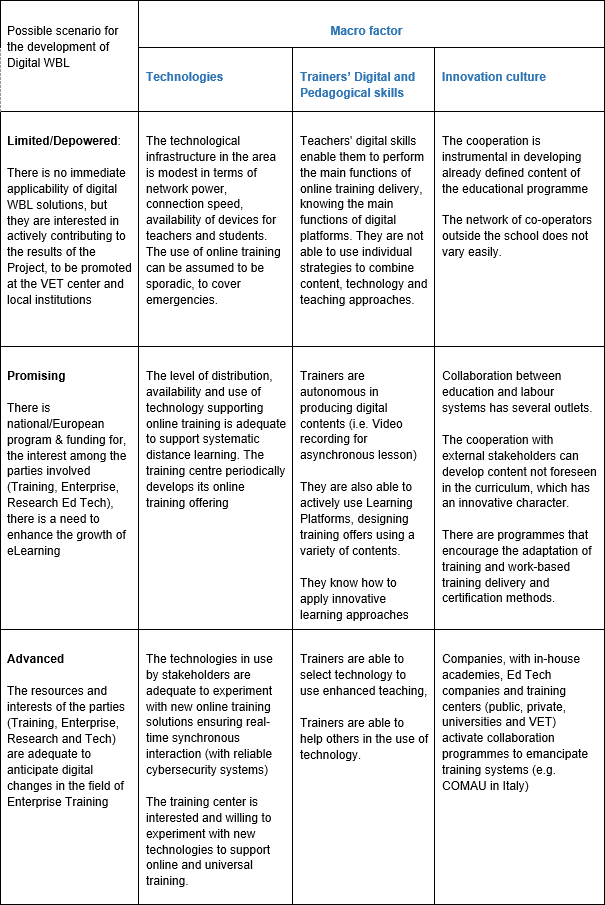

According to the partners of the Digital WBL project profiles, and thanks to the stakeholders contribution given during the initial Focus Groups, the need to consider different scenarios of applicability of digital solutions for the delivery of work-based learning is evident.

To make the project results effectively sustainable in the different contexts, the project staff outlined three possible application scenarios of digital WBL results, considering the different levels of development of some macro factors as outlined below.

Macro factor 1: Connectivity and Technologies: it means having an adequate degree of digital maturity locally to support the use of digital systems in education. Indicators for this factor could include: the presence of fibre optic infrastructure, 5G coverage, no. of available digital devices per inhabitant, no. of mobile broadband take-up (compare DESI – Digital Economy and Society Index https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi). This factor allow to profile the technologies currently available at the training centers, the investments that the training center is interested in making for technology improvement.

Macro factor 2: Teachers’ and students skills, including digital skills to govern digital and virtual learning environments and the ability to apply innovative pedagogies and training approaches, centered on the learning objectives and the learning that the student can achieve, rather than on the curriculum.

Macro factor 3: Culture of innovation supported by the Training organization. It means how the training center supports teachers, students in bringing innovative elements into teaching. It can be measured by identifying the n. of extra-curricular projects that are carried out in a year, the n. of collaborations that the training center activates with local players for the realization of curricular or extracurricular projects (companies, research and territorial development centers, Digital Innovation Hubs, etc.), the networks between “Education – Enterprise and Research” the Training center manages .

Based on the level of development that each macro-factor presents, we have identified 3 ‘ideal’ levels of applicability.

With respect to these three levels, the guidelines will report different levels of applicability of solutions to achieve the objectives of the Digital WBL project, and will invoke differentiated commitments and resources with which the different partners can address and develop their own levels of digital WBL.

[1] 2022, Mc Kinsey & Company “How technology is shaping learning in higher education” https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/how-technology-is-shaping-learning-in-higher-education